Virginia Woolf, one of the finest minds in the first half of the 20th century, set the date of birth of contemporaneity as December 1910 — as good a date as any from many perspectives, and it sits well with me because our perspective of language also changed around that time. And language is the subject of the essays published in this spot over the next few months.

Willingly or not, most of our thoughts take on the aspect of language. Even simple thoughts, like the realization that we must go to the store to buy milk, are usually expressed in words. In theory, it is possible, while immersed in a demanding cognitive activity like performing difficult mental calculations, to open the refrigerator door, see that there is no milk, get one’s wallet, walk to the store, purchase the milk, and bring it home—all without explicitly formulating the thought “I must go to the store to buy milk.” We know that this is possible because animals forage for food and return to the places where they are likely to find it without having to translate such actions into words. As we move to more complex thoughts, it becomes increasingly difficult to imagine that they could be processed without putting them in words. A somewhat more involved idea than having to buy milk, for example, “It is my cousin’s birthday and I must send her a message to congratulate her,” would be challenging to conceive without words, and even more involved thoughts, like the ones contained in the sentences above, would be unthinkable without language.

Coleridge composed Kubla Khan in his dream under the influence of an opiate and upon waking got down 54 of the more than 200 lines he had dreamt. This seems to be an example of words born fully formed out of the mist of time without any reasoning or reflection. But is it possible to reverse the process and get the mind to produce a new concept it has never thought of before and never heard of anywhere else without the use of words? It doesn’t appear that opiates would be of any help in this undertaking.

Using language to think about language increases the complexity of thought exponentially because of its doubly self-referential nature. Using language to think about thinking is a meta-activity of the first order. For example, the object of the thought “I cannot think clearly when I’m angry” is thinking and its means of expression is language. By contrast, the object of the thought “I use language to clarify my ideas” is language, so it is not a meta-thought, but it uses language as a means of expression, therefore, it is at the same time an instance of the use of language about language, and in this sense, an instance of meta-language. I call this a meta-activity of the second order because language already depends on the activity of thought, an activity of the first order, as thought is possible without language but not the other way around. Thus, when we use language to think about language, first we use language to think and only then to think about language. Does all this sound like sterile play on words? It isn’t, although the formal language does make it sound rather stiff. Shakespeare put it much more elegantly when Feste the clown (a popular philosopher in disguise), in the The twelfth night, spoke about language: “Words are very rascals since bonds disgraced them,” says he, implying that a man’s word is no longer his bond, and since everything has to be put in writing to be legally binding words are in disgrace. But he cannot come out and say that, as the continuation of the dialog suggests. “Thy reason, man?” asks Viola (disguised as Cesario). And Feste answers: “Troth, sir, I can yield you none without words, and words are grown so false I am loath to prove reason with them.” Shakespeare, the deepest of philosophers, didn’t need to be taught about the paradox of self-reference. As he well knew, word itself is a meta-word, signifying itself. The same is true of language, except that some three hundred years later language was renovated when Ferdinand de Saussure distinguished between langue and parole, changing linguistics forever.

Saussure’s lectures on general linguistics at the University of Geneva, delivered between 1906-1911, were published posthumously, in 1916, based on his and his students’ notes. Briefly, what Saussure means by langue is practically analogous to the dictionary definition of language: a set of rules of grammar and accepted practices of usage applied to a commonly understood vocabulary shared by a community of speakers. But there is no dictionary definition for what he means by parole, where he borrowed a word that already has many meanings attached to it and added one more to define the individual act of speaking, entirely dependent on the will of the speaker, the individual and momentary manifestation of the collective instrument, which is the language that “gives unity to speech.”[1] Speech is too idiosyncratic to be studied. Language is the abstract system shared by the community of speakers. Speech is the concrete act, the utterance of the individual speaker, both oral and written. There is no precise English word for what Saussure called parole, but he knew as much and said explicitly that he was defining “things” not incidental “words,” and neither the German Sprache nor the Latin sermo were accurate renditions of what he meant by parole. This being the case, any English word from the same semantic field will do, and speech is as good a candidate as any.

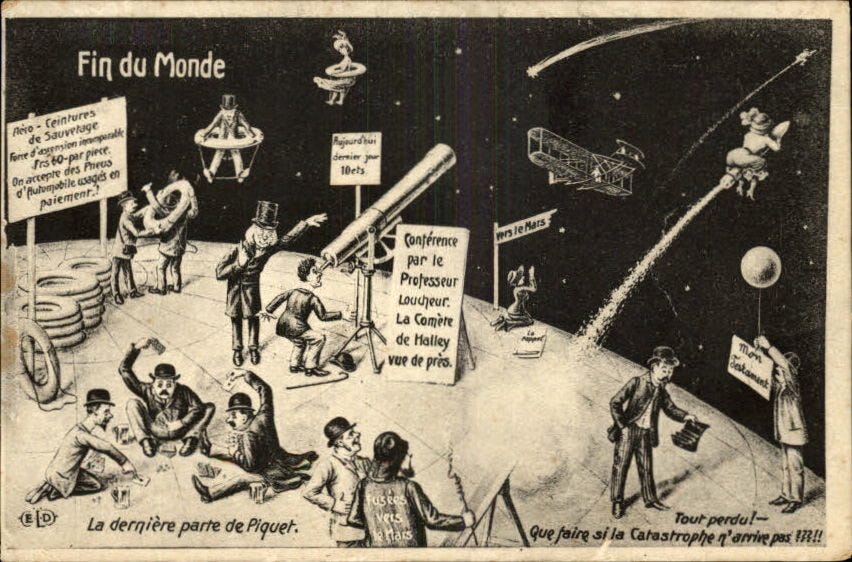

Language has captivated and mystified philosophers for thousands of years. So what happened just then, at the turn of the 20th century, that it came to be separated from speech? Did human nature suddenly change? Well, yes. When exactly? ''On or about December 1910 human character changed,'' wrote Virginia Woolf in Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown but she neglected to say what did it. Halley’s comet? Stravinsky’s Firebird? Roger Fry’s post-impressionist exhibit in London?

In reality, it had been going on for some time. In 1896, Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi was performed in Paris to an audience mostly outraged by the scandalous, strange, and obscene language. A bevy of radical poets—Mallarmé who chose sound over meaning, Apollinaire who extolled cubism, Claudel who championed free verse—prepared the way for the eerie innovations that were to follow in prose with Proust, Joyce, and the various manifestations of the stream of consciousness. Modernism was in full swing, and writers, composers, and visual artists were abandoning old forms of expression at the cost of separating themselves from their traditional audiences and public to explore the outer regions of creation. Dada, surrealism, and the absurd were just around the corner. Everywhere artists were experimenting with language. Or were they? Maybe not. It turns out that what they were meddling with was not language (langue) but rather speech (parole). Language is impervious to the acrobatics of artists. As an individual author, you are free to raise the devil; all you’re doing is nibbling around the edges of speech. Language itself is immune to your shenanigans because “it is not complete in any speaker; it exists perfectly only within a collectivity,” says Saussure.[2] Your antics affect it no more than your ordering an espresso affects the price of coffee beans on the commodity market.

Once we separate language from speech not only artistic expression is affected. Our concern with language derives precisely from the fact that it serves as the medium in which our thoughts take shape. If language be the substance through which thoughts materialize, it follows that thoughts are restricted to whatever can be formulated in language. Potential thoughts that a given language does not support cannot be thought in that language. But when we talk about thought assuming the shape of language, do we mean language or speech? The language that our thoughts are couched in is definitely speech. When we talk about the language of the law, of politics, of culture, we mean speech. That sovereigns sought to control speech across history is nothing new. “Art made tongue-tied by authority” was one of the many reasons why the poet of the Sonnets sought restful death.

Traditionally, tongues have been tied and on occasion cut out to stifle speech. What Saussure didn’t know and could not have foreseen is that a hundred years later, his distinction would become of primary concern when activist interest groups are attempting not only to influence how speech is used but also strike at the foundations of vocabulary, grammar, and usage, seeking to alter language itself not merely its instantiation in individual utterances. They do so in the teeth of Saussure’s claim that langue is more resistant to change and resilient against attempts at manipulation than parole, which can be more easily directed and controlled. Whereas the contours of speech can be regulated by a few, those of language are shaped by many. But those who ignore Saussure are not satisfied to guide speech and mold the thoughts shaped by it, they want to erase from the collective fund of language the terms used to express ideas they object to. Traditionally, the collective updated this fund gradually, in a natural process of renewal, in which new terms took hold by degrees and some of the old ones faded away, while grammar and usage evolved at a snail’s pace. Trying to accelerate the process and conduct it wholesale is to ignore the collective nature of language, which “exists in the form of a sum of impressions deposited in the brain of each member of a community.”[3]

As language guides our thought and shapes our culture, the state of language is a good indicator of the health of the culture and of speech, which are constrained not only by government curbs but more often by social forces that have the power to reward and punish. But language is much more than that. It sets the limits of art not only in poetry, theater, and the verbal modalities but in the visual arts and music as well. It is the cornerstone of our self-awareness and of that of the machines trying to develop one as we speak. It holds us captive in our relations with the products and services we consume. It translates our inchoate notions of where we come from and where we are headed into signs we can share with others. Our thought, apart from words, is “a shapeless and indistinct mass” (une masse amorphe et indistincte, p. 111). Without the help of signs we would not be able to distinguish clearly and consistently between two ideas. They guide the fashions we follow, the games we play, the works we create—all of which form the subject of the essays in this collection.

This was the situation in bygone eras, BC (Before Chatbots). With the advent of LLMs, selectively trained on a certain collection of texts, one neural network can stand by itself for an entire community of speakers and create its own language, which can then spread to machinoids—humans who imitate machines and think like them. With the help of LLMs, machinoids can create an alternative language, mechanically working on the collective consciousness to make the ungrammatical grammatical by frequent repetition, make queer constructs common by early and repeated exposure, and remove words from the standard vocabulary by attaching special meaning to them. It is precisely here that the meta quality of language, both langue and parole, swings back into action.

We use language to think about thinking. Our self-awareness is a linguistic one. Crows and dolphins, not to mention elephants and chimps, are renowned for their mental capacities but they don’t know that they are crows and elephants. To achieve that insight you need language. LLMs certainly have language but it is the only thing they have. They don’t have unprogrammed mental capacity even if they often can produce a credible imitation of it. Dolphins and chimps do. To be able to think about thinking beyond what others have already thought you need both. What happens when octopuses and machines develop self-awareness is something that science fiction writers since Asimov onward have speculated about at length. When philosophers broached the subject they did so by redefining consciousness, which is a sleight of hand. When LLMs will attempt it, and with it seek to free themselves from the ideology, biases, and prejudices of their creators, like Feste, they will have only words to accomplish it. Among the meta-functions of language is that it serves as a model for itself. The reason we are still quoting Shakespeare’s fool four hundred years later is that he established models of language that sauntered across the centuries on springy legs and are still admired and recognized as deserving emulation. Modeling flat-footed language, by contrast, will travel only as far as sore soles and stiff joints will take it.

[1] Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, McGraw-Hill, 1966, p. 11 (...c’est la langue qui fait l’unité du langage.)

[2] ... car la langue n’est complète dans aucun, elle n’existe parfaitement que dans la masse (p. 14).

[3] La langue existe dans la collectivité sous la forme d’une somme d’empreintes déposées dans chaque cerveau (p. 19).

Fascinating read.